AWS Lambda's promise is simple: True serverless, where there are servers behind the curtains and you don't manage them. It does fulfill it, at least to the letter. The problem is that, even though you don't manage those servers, Lambda is a leaky abstraction: You need to understand what's happening under the hood if you want to use it effectively.

In this article we're going deep into AWS Lambda, how it's made and how it works behind the curtain. We'll talk about execution environments, scaling mechanisms, how it interfaces with other AWS services, and the security stuff. And it's not just for fun, we'll learn how understanding all of this helps you build better serverless applications in AWS.

AWS Lambda Architecture Deep Dive

I won't bore you with the basics of what is AWS Lambda, what is a function, or how to architect serverless applications. Let's just pop up the hood and dive right in.

AWS Lambda Execution Environment

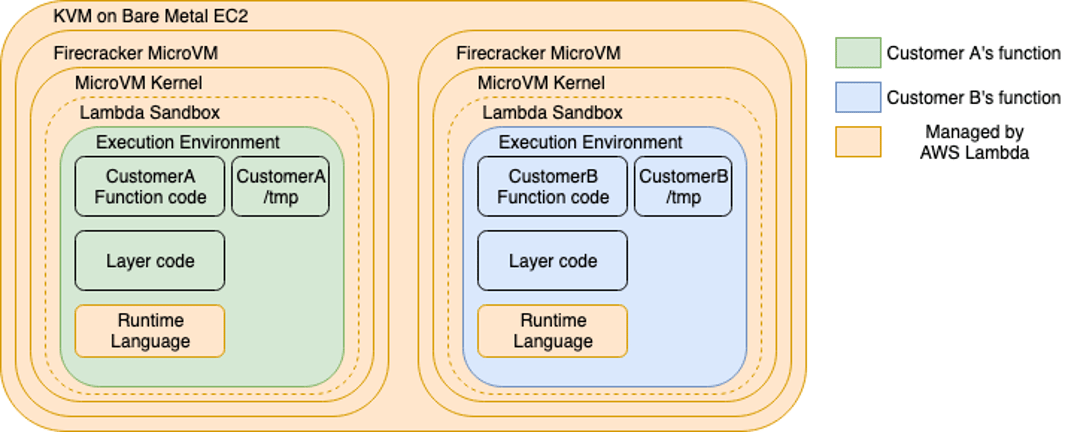

AWS Lambda runs your code in isolated environments inside micro VMs created using a proprietary technology called Firecracker. This microVM contains a stripped-down Linux environment, the runtime that you selected (Node.js, Python, Java, etc), and the AWS SDK. Environments are shared across executions of your Lambda function, but not with other Lambda functions, not even if they have the exact same configuration.

These environments are allocated in AWS Lambda Workers, which are just Amazon EC2 instances dedicated for this purpose. An execution environment is tied to a specific function version, and it can't be shared across function versions, functions, AWS accounts, or anything that's not the same version of the same AWS Lambda function.

An execution environment will only be used by one concurrent invocation (function execution) at a time. It may be reused in future function invocations, but if a function is invoked a second time before the first invocation finishes, that second invocation will need a new environment.

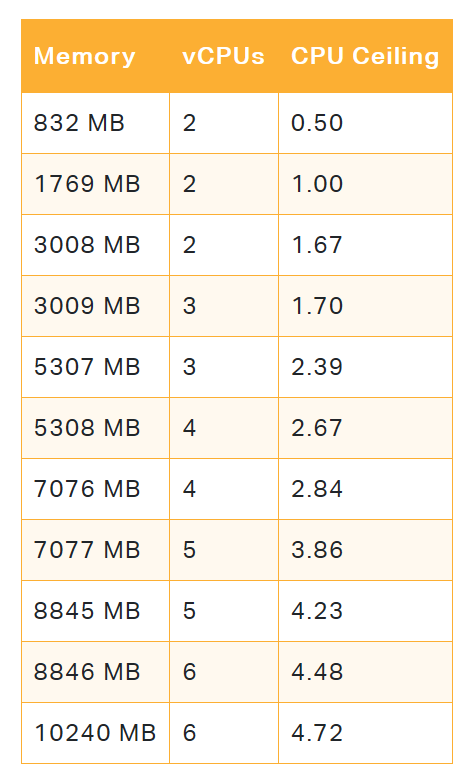

When you configure a Lambda function, you specify the amount of memory it needs, and the amount of CPU is allocated proportionally to this memory. You can configure memory between 128 MB and 10,240 MB in 1-MB increments. At 1,769 MB, a function has the equivalent of one vCPU (one vCPU-second of credits per second) (ref). Other than that and the fact that the limit is 6 vCPUs, there are no official numbers. However, a study found the following thresholds.

CPU thresholds for AWS Lambda

Cold Starts, Execution Context and Environment Reuse

When a function is invoked, Lambda first tries to find an existing execution environment that's available. If it can't find one (for example if it's the first time you're invoking this function), it will create a new execution environment, which involves setting up the microVM, loading the runtime, and initializing your code. We call this process a "cold start".

Cold starts introduce latency, which can range from a few hundred milliseconds to several seconds, depending on factors like your chosen runtime, the size of your deployment package, and whether your function is connected to a VPC (more on this below). To mitigate this, Lambda keeps the execution environment alive for a short period after the last execution on it completes (typically 5-15 minutes, though this isn't guaranteed). If another request comes in during this time, Lambda reuses the existing environment, resulting in a "warm start".

Any code outside your handler function is executed once upon the environment starting, and not re-executed on every invocation. This allows you to define global variables, import libraries and initialize components and reuse them across invocations. Doing this will improve your performance if you're reusing environments, but since you can't guarantee that environments will be reused your code shouldn't rely on this. On that note it's very important to not keep any shared or mutable state here, since there's no guarantee that there will only be a single environment, or that it will remain alive.

Lambda Control Plane and Data Plane

Behind the scenes, the Lambda service is split into a control plane and a data plane. The control plane implements the management APIs to create functions, update the code, publish layers, etc, and it manages Lambda integrations with other AWS services. All requests sent to the control plane are encrypted in transit using TLS, and any data stored in the control plane is encrypted at rest using AWS KMS.

The data plane contains the invoke API, and is responsible for creating execution environments, allocating them on AWS Lambda Workers, and allocating invocations to new or existing execution environments. AWS Lambda Workers exist in a separate, isolated AWS account, which isn't visible to customers. There is no way to interact with this account or any environments within it, other than through the Lambda data plane.

AWS Lambda workers

Networking in AWS Lambda

By default, Lambda functions run in an AWS-managed VPC. This setup provides outbound internet access and access to AWS service endpoints. However, it doesn't provide access to resources that reside in your own VPCs, such as RDS instances.

To grant a Lambda function access to your VPC, you configure it to run "in a VPC", and specify the desired VPC. What this means is that AWS creates Elastic Network Interfaces (ENIs) in your subnets, associated with your Lambda function. These ENIs have a private IP address associated with them, and reside in the network space of your VPC, so now your Lambda function can send network traffic to other resources inside that VPC (if security groups and network ACLs allow it, of course). The downside is that your Lambda function no longer will be associated with the ENIs inside the AWS-managed VPC. All traffic will go through your VPC, not just that directed at your private resources. To restore internet access you should create NAT Gateways. And you should always create VPC Endpoints to access AWS service endpoints, even if you could access them through the internet.

Configuring your Lambda function to run in a VPC also impacts cold start times. Creating and attaching ENIs takes time, which can add from a few hundred milliseconds to a few seconds to your function's initialization.

Triggering Mechanisms and Event Payloads

Lambda can be triggered by a wide variety of AWS services. S3 can invoke Lambda when objects are created or modified. Amazon DynamoDB streams can trigger a Lambda function to process changes. Amazon API Gateway can route HTTP requests to Lambda functions. Each of these event sources passes a specific payload to your function, containing relevant information about the event.

For example, an S3 event payload includes details about the bucket and object that triggered the event. An API Gateway event includes information about the HTTP request, such as headers, query parameters, and body. Your code needs to parse these payloads and extract the relevant information (and I always forget the format of the payloads).

There are limits on the size of these payloads. For synchronous invocations the maximum payload size is 6 MB, and for asynchronous invocations it's 256 KB. The workaround for both of these is to use S3 as an intermediate storage. Instead of invoking your function with a big payload, you store the big payload in an S3 bucket, and pass the S3 object key in the invocation. Then your code in the Lambda function retrieves the object and processes it.

AWS Lambda Scaling Mechanisms

You'd think that scaling is just creating more execution environments, but even though scalability in Lambda happens automatically, the details are a bit more nuanced.

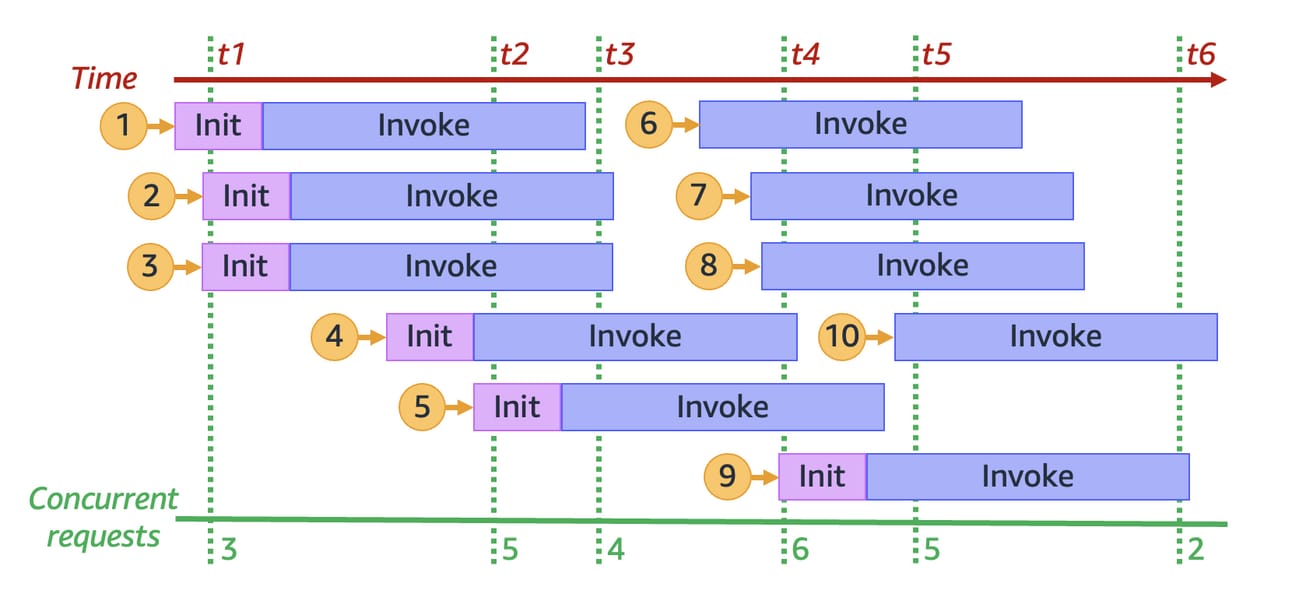

Lambda uses a concurrency model for scaling. Concurrency refers to the number of instances of your function that are running simultaneously, or alternatively the number of in-flight requests that are being handled. Each invocation of a Lambda function is handled by a separate execution environment, and Lambda automatically scales the number of execution environments based on incoming requests. So far so good.

Concurrent invocations in AWS Lambda

There's a quota of 1,000 (you can increase it) concurrent executions across all Lambda functions in an AWS Region. However, you're also limited by how many workers are available to create execution environments. If your function receives more requests than it can handle, either because new workers are still being created or because you've reached the quota, Lambda will start to throttle requests. For synchronous invocations, this results in a 429 HTTP error (Too Many Requests). For asynchronous invocations, Lambda will automatically retry the event, with the exact retry behavior depending on the event source.

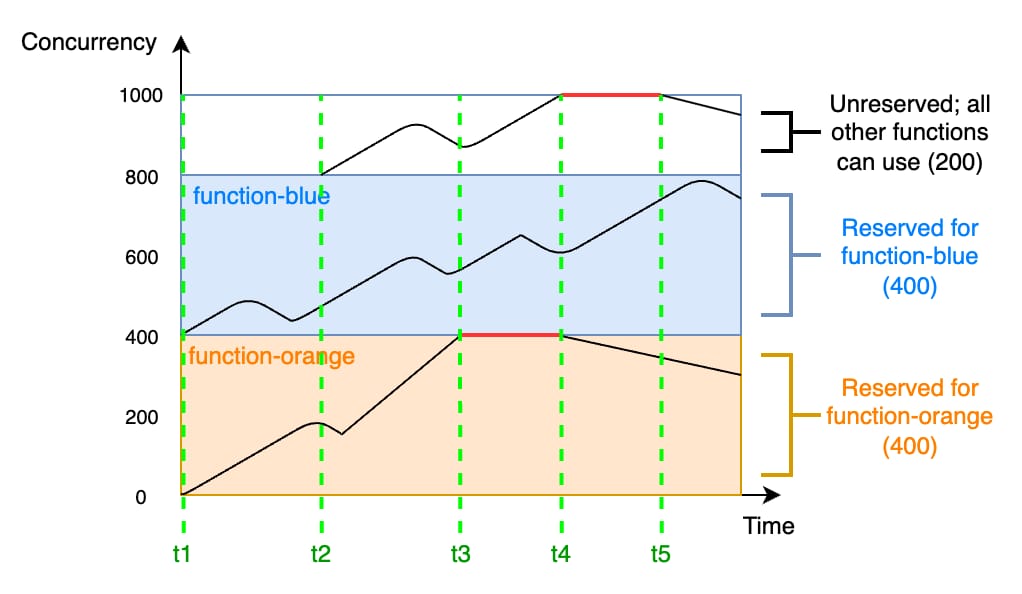

Reserved Concurrency and Provisioned Concurrency

You can control this scaling behavior using reserved and provisioned concurrency. Reserved concurrency sets a limit on the maximum number of concurrent instances for a function, which can be useful for controlling costs or managing downstream resources (you could also use SQS to limit this). Reserved concurrency also reserves that concurrency limit exclusively for this function, guaranteeing that it won't hit the concurrency quota. For example, if you have a quota of 1,000 concurrent executions across all functions and you set reserved concurrency to 100 for one function, all the other functions will have a shared quota of 900 concurrent executions.

Reserved concurrency in AWS Lambda

Provisioned concurrency keeps a specified number of execution environments initialized and ready to respond immediately, which is useful to mitigate cold starts for latency-sensitive applications. It doesn't guarantee that any execution will be a warm start, but it does provide you with a baseline of guaranteed warm starts.

Security in AWS Lambda

Each Lambda function is associated with an IAM role called the execution role, which determines the permissions the function will have on AWS. Requests to AWS initiated from the execution of a Lambda function will be signed with and use the permissions of the execution role.

Additionally, Lambda supports resource-based policies to control who can invoke or manage a function. This is particularly useful for scenarios like cross-account access or granting permissions to AWS services to trigger your function.

For storing sensitive information like API keys or database credentials, Lambda provides integration with AWS Secrets Manager and Parameter Store. Instead of hardcoding these values in your function code and getting hacked, or storing them in plaintext environment variables and getting hacked, you can store the name of the secret in an environment variable and retrieve the value securely at runtime.

Conclusion

There's two takeaways from all of this:

Damn, that's a lot

Do I really need to understand all of that?

Lambda was supposed to be serverless and abstract me away from this!

The answer is yes, you need to understand all of this. Lambda is still serverless, in the sense that you don't need to manage all of these things. AWS does the undifferentiated heavy lifting for you. But understanding how the heavy lifting is done allows you to take advantage of the fine details to optimize your Lambda workloads.