The first rule about microservices is that you don't need microservices (for 99% of applications). They were invented as a REST-based implementation of Service-Oriented Architectures, which is an XML-based Enterprise Architecture pattern so complex that XML is the easiest part.

At some point, microservices became this really cool thing that all the cool kids were doing for street cred. "Netflix does it, so if I do it I'll be as cool as Netflix!" Folks, it doesn't work like that.

What Are Microservices?

A microservice is a service in a software application which encapsulates a bounded context (including the data), can be built, deployed and scaled independently, and exposes functionality through a clearly defined API.

Let's expand a bit on each characteristic:

Bounded context: The concept stems from Domain-Driven Design's bounded contexts, and essentially advocates for dividing the entire domain into several smaller domains. Microservices takes it a step further: each microservice is part of only one bounded context, and owns that context, including all domain entities, all data, and all operations and functionality. Anything that needs to access that bounded context needs to do so through the microservice's API. Conceptually, it's similar to encapsulation in Object-Oriented Programming, but on a higher level.

Built, deployed and scaled independently: Each microservice is independent in every sense. It can be built by a separate team using different technologies, it has its own deployment pipeline and process, and it can be scaled independently of the rest of the system. This provides a clear separation between what the microservice does and how it does it, and gives you a lot of flexibility on that how.

Clearly defined API: One microservice can't solve everything, or it would be just a monolith. You need several, and you need to combine them to realize the entire system's functionality. That means, you need a clear and unambiguous way to communicate with a microservice. The API is the interface of the microservice, and it's the only thing that other components of the system can access. This minimizes dependencies between microservices, letting them be implemented and evolved separately, so long as they adhere to their API. Keep in mind that, since each microservice owns its data, the only way to access the data of a microservice is through that microservice's API. No reading directly from another microservice's database!

Why Use Microservices?

Microservices exist to solve a specific problem: problems in complex domains require complex solutions, which become unmanageable due to the size and complexity of the domain itself. Microservices (when done right) split that complex domain into simpler domains, encapsulating the complexity and reducing the scope of changes.

Microservices also add complexity to the solution, because now you need to figure out where to draw the boundaries of the domains, and how the microservices interact with each other, both at the domain level (complex actions that span several microservices) and at the technical level (service discovery, networking, permissions).

So, when do you need microservices? When the reduction in complexity of the domain outweighs the increase in complexity of the solution.

When do you not need microservices? When the domain is not that complex. In that case, use regular services, where the only split is in the behavior (i.e. backend code). Or stick with a monolith, Facebook does that and it works pretty well, at a size we can only dream of.

Types of Microservices

There's two ways in which you can split your application into microservices:

Vertical slices: Each microservice solves a particular use case or a set of tightly-related use cases. You add services as you add features, and each user interaction goes through the minimum possible number of services (ideally only 1). This means features are an aspect of decomposition. Code reuse is achieved through shared libraries, and cross-service responsibilities are implemented on support microservices. This results in architectures very similar to SOA.

Functional services: Each service handles one particular step, integration, state, or thing. System behavior is an emergent property, resulting from combining different services in different ways. Each user interaction invokes multiple services. New features don't need entirely new services, just new combinations of services. Features are an aspect of integration, not decomposition. Code reuse is often achieved through invoking another service. This is often much harder to do, both because of the difficulty in translating use cases into reusable steps, and because you need a lot of complex distributed transactions.

Overall, vertical slices is easier to understand, and easier to implement for smaller systems. The drawback is that if your system does 200 different things, you'll need 200 services, plus support services and libraries. Functional services are harder to conceptualize, and it's not uncommon to end up with a ton of microservices that have 50 lines of code and don't own any data. If that's your case, you're doing it wrong. Remember that the split should be at the domain level, not at the code level. It's perfectly ok for a microservice to be implemented with several services!

Don't combine these two types of microservices! If you're doing vertical slices, support microservices should be only for non-business behavior, such as logging. If you're doing functional microservices, don't create a service that just orchestrates calls between other microservices; either use an orchestrator for all transactions, or choreograph them. And don't even think about migrating from one type of microservices to the other one. It's much, much easier to just drop the whole system and start from scratch.

Splitting a Monolith into Microservices

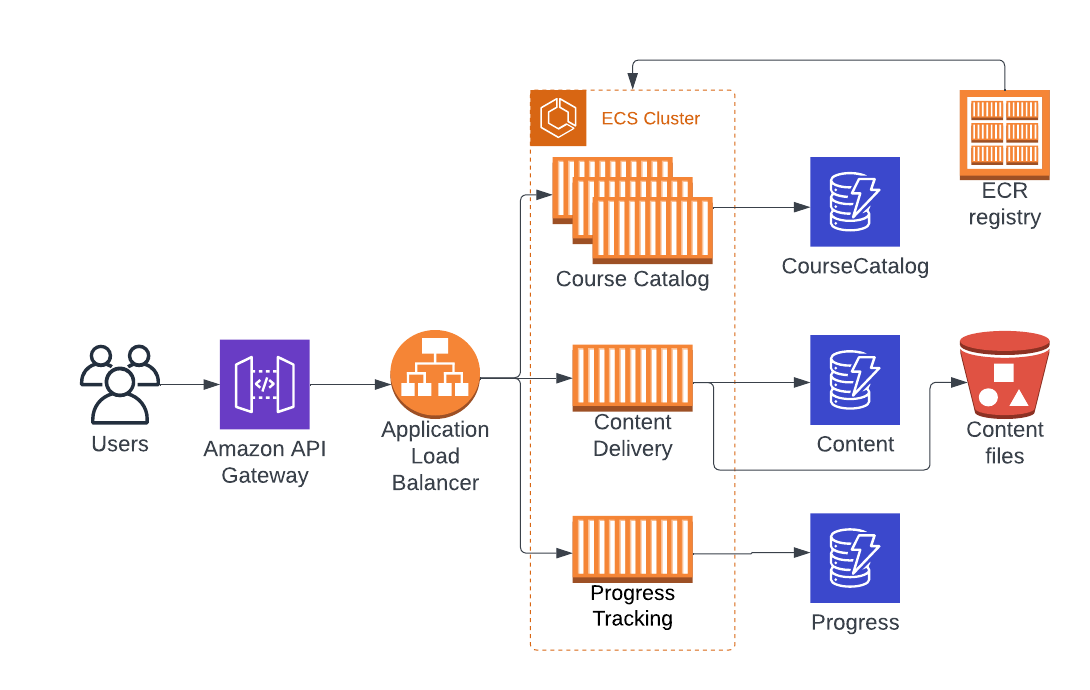

Let's see microservices in a real example. Picture the following scenario: We have an online learning platform built as a monolithic application, which enables users to browse and enroll in a variety of courses, access course materials such as videos, quizzes, and assignments, and track their progress throughout the courses. The application is deployed on Amazon ECS as a single service that's scalable and highly available.

As the app grew, we've noticed that content delivery becomes a bottleneck during normal operations. Additionally, changes in the course directory resulted in some bugs in progress tracking. To deal with these issues, we decided to split the app into three microservices: Course Catalog, Content Delivery, and Progress Tracking.

Out of scope (so we don't lose focus):

Authentication/authorization: When I say “users” I mean authenticated users. We could use Cognito to secure access to microservices, but let's focus on designing the microservices first.

User registration and management: Same as above.

Payments: Since our courses are so awesome, we should charge for them. We could use a separate microservice that integrates with a payment processor such as Stripe.

Caching and CDN: We should use CloudFront to cache the content, to reduce latency and costs. We'll do that in a future issue, let's focus on the microservices right now.

Frontend: Obviously, we need a frontend for our app. Let's keep the focus on the microservices, but if you're interested in frontend you might want to check out AWS Amplify.

Database design: Let's assume our database is properly designed. If you're interested in this topic, you should read DynamoDB Database Design.

Admin: Someone has to create the courses, upload the content, course metadata, etc. The operations to do that fall under the scope of our microservices, but I feared it would grow too complex, so I cut those features out.

AWS Services involved:

ECS: Our app is already deployed in ECS as a single ECS Service, we're going to split it into 3 microservices and deploy each as an ECS Service. We won't dive deep into ECS, but if you're interested you can learn about how to deploy a Node.js application on ECS.

DynamoDB: Our database for this example.

API Gateway: Used to expose each microservice.

Elastic Load Balancer: To balance traffic across all the tasks.

S3: Storage for the content (video files) of the courses.

ECR: A Docker registry managed by AWS.

Final design of the app split into microservices

How to Split a Monolith Into Microservices

Step 0: Make the Monolith Modular

The first step should always be to make sure your monolith is already separated into modules with clearly defined responsibilities. Modules should be well scoped, both in terms of functionality and in the code that implements that functionality. They should be cohesive, and lowly coupled to other modules. The level of granularity doesn't matter much, though ideally you'd be splitting modules according to the concept of domains from Doman-Driven Design (you don't need to apply the entirety of Domain-Driven Design). However, you can refine the scope and granularity when you start with microservices. For now, what's important is that you have clearly defined modules with clearly defined responsibilities, instead of a bowl of spaghetti code.

For this example we're going to assume this is already the case, but if you're dealing with a monolith that's not well modularized, that should be the first thing you do. If you commit all the way to microservices, you won't really use the modular monolith. However, I still recommend you first work on separating it into modules, to make the overall process easier by tackling one thing at a time.

Step 1: Identify the Microservices

Start by analyzing the monolithic application, focusing on the course catalog, content delivery, and progress tracking functionalities. Based on these functionalities, outline the responsibilities for each microservice:

Course Catalog: manage courses and their metadata.

Content Delivery: handle storage and distribution of course content.

Progress Tracking: manage user progress through courses.

Step 2: Define the APIs for each microservice

Once you understand what each microservice needs to do, you need to design the API endpoints for each microservice:

Course Catalog:

GET /courses→ list all coursesGET /courses/:id→ get a specific course

Content Delivery:

GET /content/:id→ get a pre-signed URL for a specific course content

Progress Tracking:

GET /progress/:userId→ get a user's progressPUT /progress/:userId/:courseId→ update a user's progress for a specific course

API endpoints are how microservices define and expose their functionality to external components. Essentially, the API is what a microservice can do for the user or for other microservices. We already knew the responsibilities of each microservice from Step 1, with this step we're expressing them in technical terms that other components can understand. We're also documenting them in a clear and unambiguous way.

If you're starting from a well-designed modular monolith, these APIs already exist as the APIs for services and interfaces for components, and you're just re-expressing them in a different, unified way. If the starting monolith isn't well modularized, you may find some of these APIs as functions, and you may need to add a few. In those cases it's easier to first modularize the monolith, then split it into microservices.

API design is really important, and hard to do. We're not just splitting the entire app's responsibilities into groups that we call microservices. We're actually creating several apps, that we're then going to interconnect to produce the expected system behavior. We need to not only define those apps' responsibilities well, but also design them in a maintainable way. Check out Fowler's post on consumer-driven contracts for some deeper insights.

Step 3: Configure API Gateway for each microservice

Create an API Gateway resource for each microservice (Course Catalog, Content Delivery, and Progress Tracking). Point the different routes to your monolith's APIs for now, since we don't have any microservices yet. Update any frontend code or DNS routes to resolve to the API Gateways.

This isn't a strict requirement, but I added it as part of the solution because it makes the switchover much easier: All we need to do is update the API Gateway of each microservice to point to the newly deployed microservice. Since everything else already depends on that API Gateway for that functionality, we're just changing who's resolving those requests. This way, we've effectively decoupled the API from its implementation. API Gateway also makes other things much easier, such as managing authentication for microservices.

Step 4: Create separate repositories and projects for each microservice

Set up individual repositories and Node.js projects for Course Catalog, Content Delivery, and Progress Tracking microservices. Structure the projects using best practices, with separate folders for routes, controllers, and database access code. You know the drill.

This is just the scaffolding, moving the actual code comes in the next step. The key takeaway is that you treat each microservice as a separate project. You could also use a monorepo, where the whole codebase is in a single git repository, each service has its own folder, and it's still deployed separately. This works well when you have a lot of shared dependencies, but in my experience it's harder to pull off.

Step 5: Separate the code

Refactor the monolithic application code, moving the relevant functionality for each microservice into its respective project:

Move the code related to managing courses and their metadata into the Course Catalog microservice project.

Move the code related to handling storage and distribution of course content into the Content Delivery microservice project.

Move the code related to managing user progress through courses into the Progress Tracking microservice project.

The code in the monolith may not be as clearly separated as you might want. In that case, first refactor as needed until you can copy-paste the implementation code from your monolith to your services (but don't copy it just yet). Then test the refactor. Finally, do the copy-pasting.

Step 6: Separate the data

First, create separate Amazon DynamoDB tables for each microservice:

CourseCatalog: stores course metadata, such as title, description, and content ID.

Content: stores content metadata, including content ID, content type, and S3 object key.

Progress: stores user progress, with fields for user ID, course ID, and progress details.

Then update the database access code and configurations in each microservice, so each one interacts with its own table.

Remember that the difference between a service and a microservice is the bounded context. Each microservice owns its domain model, including the data, and the only way to access that model (and the database that stores it) is through that microservice's API.

We could implement this separation of data at the conceptual level, without enforcing it through separate tables. We could even enforce it while keeping all data in a single table, using DynamoDB's field-level permissions. The problem with that idea (aside from the permissions nightmare) is that we wouldn't be able to scale the services independently, since DynamoDB capacity is managed per table.

If you're doing this for a database which already has data, but you can tolerate the system being offline during the migration, you can export the data to S3, use Glue to filter the data, and then import it back to DynamoDB.

If the system is live, this step gets trickier. Here's how you can split a DynamoDB table with minimal downtime:

First, add a timestamp to your data if you don't have one already.

Next, create the new tables.

Then set up DynamoDB Streams to replicate all future writes to the new table. You'll need to set one stream per microservice. It's easier if you set it up to copy all the data and after the switchover you delete the irrelevant data. But if you're performing a lot of writes, it will be cheaper to selectively copy only the data that belongs to the microservice.

Then copy the old data, either with a script or with an S3 export + Glue (don't use the DynamoDB import, it only works for new tables, write the data manually instead). Make sure this can handle duplicates.

Finally, switch over to the new tables.

I picked DynamoDB for this example because DynamoDB tables are easy to create and manage (other than designing the data model). In a relational database we would need to consider the tradeoff between having to manage (and pay for) one DB cluster per microservice, or having different databases in the same cluster. The latter is definitely cheaper, but it can get harder to manage permissions, and we lose the ability to scale the data stores independently. Aurora Serverless is a viable alternative, it scales very similarly to DynamoDB in Provisioned Mode. However, it's 4x more expensive than serverful Aurora.

Step 7: Build and Deploy the Microservices

We're using ECS for this example, just so we can focus on the microservices part, instead of debating over how to deploy an app. These are the steps to deploy in ECS, which you'll need to do separately for each microservice:

Write a Dockerfile specifying the base image, copying the source code, installing packages, and setting the appropriate entry point. Test this, obviously.

Build and push the Docker image to an Amazon Elastic Container Registry (ECR) registry. You'll use a separate registry for each microservice (remember they're separate apps).

Create a Task Definition in Amazon ECS, specifying the required CPU, memory, environment variables, and the ECR image URL.

Create an ECS service, associating it with the corresponding Task Definition. Make sure this is working properly.

I don't want to dive too deep into how to deploy an app to ECS. If you're not sure how to do it, here's an article I wrote about it.

Step 8: Update API Gateway

For each API in API Gateway, you'll need to update the routes to point to the newly deployed microservice, instead of to the monolith. First do it on a testing stage, even if you already ran everything in a separate dev environment. Then configure a canary release, and let the microservice gradually take traffic.

You might want to preemptively scale the microservice way beyond the expected capacity requirement. One hour of overprovisioning will cost you a lot less than angry customers.

User Interaction in the Monolith vs in Microservices

Here's the journey for a user viewing a course in our monolith:

The user sends a login request with their credentials to the monolithic application.

The application validates the credentials and, if valid, generates an authentication token for the user.

The user sends a request to view a course, including the authentication token in the request header.

The application checks the authentication token and retrieves the course details from the Courses table in DynamoDB.

The application retrieves the course content metadata from the Content table in DynamoDB, including the S3 object key.

Using the S3 object key, the application generates a pre-signed URL for the course content from Amazon S3.

The application responds with the course details and the pre-signed URL for the course content.

The user's browser displays the course details and loads the course content using the pre-signed URL.

And here's the same functionality in our microservices:

The user sends a login request with their credentials to the authentication service (not covered in the previous microservices example).

The authentication service validates the credentials and, if valid, generates an authentication token for the user.

The user sends a request to view a course, including the authentication token in the request header, to the Course Catalog microservice through API Gateway.

The Course Catalog microservice checks the authentication token and retrieves the course details from its Course Catalog table in DynamoDB.

The Course Catalog microservice responds with the course details.

The user's browser sends a request to access the course content, including the authentication token in the request header, to the Content Delivery microservice through API Gateway.

The Content Delivery microservice checks the authentication token and retrieves the course content metadata from its Content table in DynamoDB, including the S3 object key.

Using the S3 object key, the Content Delivery microservice generates a pre-signed URL for the course content from Amazon S3.

The Content Delivery microservice responds with the pre-signed URL for the course content.

The user's browser displays the course details and loads the course content using the pre-signed URL.

Best Practices for Microservices on AWS

Operational Excellence

Centralized logging: You're basically running 3 apps. Store the logs in the same place, such as CloudWatch Logs (which ECS automatically configures for you).

Distributed tracing: These three services don't call each other, but in a real microservices app it's a lot more common for that to happen. In those cases, following the trail of calls becomes rather difficult. Use X-Ray to make it a lot simpler.

Security

Least privilege: It's not enough to not write the code to access another service's data, you should also enforce it via IAM permissions. Your microservices should each use a different IAM role, that lets each access its own DynamoDB table, not

*.Networking: If a service doesn't need network visibility, it shouldn't have it. Enforce it with security groups.

Zero trust: The idea is to not trust agents inside a network, but instead authenticate at every stage. Exposing your services through API Gateway gives you an easy way to do this. Yes, you should do this even when exposing them to other services.

Reliability

Circuit breakers: User calls Service A, Service A calls Service B, Service B fails, the failure cascades, everything fails, your car is suddenly on fire (just go with it), your boss is suddenly on fire (is that a bad thing?), everything is on fire. Circuit breakers act exactly like the electric versions: They prevent a failure in one component from affecting the whole system. I'll let Fowler explain.

Consider different scaling speeds: If Service A depends on Service B, consider that Service B scales independently, which could mean that instances of Service B are not started as soon as Service A gets a request. Service B could be implemented in a different platform (EC2 Auto Scaling vs Lambda), which scales at a different speed. Keep that in mind for service dependencies, and decouple the services when you can.

Performance Efficiency

Scale services independently: Your microservices are so independent that even their databases are independent! You know what that means? You can scale them at will!

Rightsize ECS tasks: Now that you split your monolith, it's time to check the resource usage of each microservice, and fine-tune them independently.

Rightsize DynamoDB tables: Same as above, for the database tables.

Cost Optimization

Optimize capacity: Determine how much capacity each service needs, and optimize for it. Get a savings plan for the baseline capacity.

Consider different platforms: Different microservices have different needs. A user-facing microservice might need to scale really fast, at the speed of Fargate or Lambda. A service that only processes asynchronous transactions, such as a payments-processing service, probably doesn't need to scale as fast, and can get away with an Auto Scaling Group (which is cheaper per compute time). A batch processing service could even use Spot Instances! Every service is independent, so don't limit yourself.

Consider the increased management efforts: It's easier (thus cheaper) to manage 10 Lambda functions than to manage 5 Lambda functions, 1 ECS cluster and 2 Auto Scaling Groups.

A 4 minute explanation of Zero Trust, by its creator. Best 4 minutes you'll spend today.

If you haven't, go check the part about networking and service discovery of the ECS Workshop.

The best way to separate networking and discovery from application logic is through a Service Mesh. AWS has a service that does that, and an excellent workshop to learn about it.